It is interesting being a Latter-day Saint Biblical scholar, because so much of our scholarship is informed by our religion (other scholars are often wary of LDS scholarship and BYU scholarship in specific because of this). Of course, I think this is a good thing, since I think that religion ought to come into all parts of life. Regardless, it makes for some interesting interactions with the scholarly world. As an example to get us started, in one of my classes this term, we were discussing Jewish and Christian interpretation of the story of Cain and Abel. We examined the Midrash Rabbah, the Pirkei de R. Eliezer, Origen's Homilies on Genesis and even the Syriac Church Fathers. All of these had a number of interesting interpretations. However, as I sat there listening, I kept thinking about the Book of Moses and the story of Cain and Abel contained therein. The Book of Moses contains a number of interesting additions and interpretations to the story, from the idea that Cain wasn't the eldest child of Adam and Eve, to the whole Master Mahan principle of murdering and getting that is behind all our understanding on the character of Cain. I couldn't share these (at least not in the class) because the rest of the world doesn't recognize the antiquity of our sources.

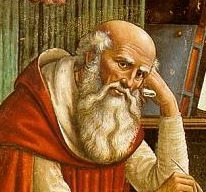

Which brings me to the idea that prompted this post--a discussion one of my colleagues presented on Origen's interpretation of the Song of Songs, which we call the Song of Solomon (for those of you not majoring in Biblical studies, Origen was a Greek Church Father, who lived in Alexandria). This book of scripture is one of the most important in all of Jewish and Christian Biblical interpretation. Rabbi Akiva, an important Jewish sage, said that if the Writings (the non-Torah, non-Prophetic portions of the Hebrew Scriptures) were Holy, then the Song of Songs was the Holy of Holies. The Targum (Aramaic translation) on the Song of Songs is six times as long as our Biblical book, showing a desire to interpret and work with the text. Even the title of the book in Hebrew, which translates to Song of Songs (which I have been referring to it by that name) speaks of how important it was to the ancients.

Yet we don't read it. Part of this comes from the fact that all the interpretations of the Song of Songs are mystical and allegorical, and the Church doesn't have a strong mystical tradition, and the allegorical interpretation tends to be somewhat secondary in our exegesis. However, I think most of our animosity (remember the persistent legend, which may indeed be true, that this or that General Authority had stapled the Song shut in his copy of the Scriptures) comes from the manuscript to the Joseph Smith Translation, which notes, rather famously, "The Song of Solomon is not inspired scripture." And there you have it. An entire book of the Bible is removed from our collective consciousness. Perhaps unfortunately. Now, I am not suggesting that the Song is, in fact, inspired scripture. Nothing could be further from the truth. I believe in the Scriptures of the Restoration. I am perfectly willing to trade a thousand Songs for one Book of Mormon. I hold that Joseph Smith was a prophet of God, and claim his New Translation as inspired scripture, so if that translation says the Song isn't inspired, then it isn't inspired. End of argument.

But not, I think, end of story. The fact that numerous writers have found in the Song a powerful metaphor for Christ and God and their relationship with the divine, and that so much ink has been spilled over this book shows that perhaps I am missing something, that there may be a beauty in this book, independent of its inspirational status. After all, as one of my Jewish friends pointed out to me as I discussed this with him, Shakespeare wasn't inspired either, but we still read his sonnets and find beauty and some level of inspiration in them. In fact our own scriptures tell us that all things testify of Christ, and we go out of way to find gospel principles in Lord of the Rings, Star Wars and rock and roll. We examine the relationship between God and man in Dante and Milton, and find the grandeur of God in Blake. But we don't read or study the Song of Songs. I think probably because it is in our Bible, and since it is not inspired it is somehow masquerading as scripture, so we don't read it, lest any think that we are somehow endorsing it as scripture, somehow restoring to it a validity that Joseph Smith took from it, correctly, I once again hasten to add. I don't know.

Once again, I don't think we should all go out and read the Song of Songs. These are just some thoughts I was thinking on subsequent to my class, which I wanted to share with you my faithful reader. While I am sharing things, I will share this touching quote from Origen which inspired this whole discussion:

"The Bride then beholds the Bridegroom; and He, as soon as she has seen Him, goes away. He does this frequently throughout the Song; and that is something nobody can understand who has not suffered it himself. God is my witness that I have often perceived the Bridegroom drawing near me and being most intensely present with me; then suddenly He has withdrawn and I could not find Him, though I thought to do so. I long, therefore, for Him to come again, and sometimes He does so. Then, when He has appeared and I lay hold of Him, He slips away once more; and, when He has slipped away, my search for Him begins anew."

Excelsior.

Thursday, December 06, 2007

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

3 comments:

I have wondered about the comments of the Song of Solomon. Which often is called pornographic and obscene. However despite the fact this is not inspired scripture it remains in the bible.

The Song of Solomon hearkens in my opinion to the older mystic traditions among the Semitic peoples. Similar writing is found in the the styling of Moorish poetry and in the wittings of the Kabala. The metaphor seeks to take to take what Puritan inspired Christians would call base and elevates them in communion with God. Consider some of the implications.

Mormons consider sex to be a act with which we are co-creators with the father. Could not Sex then be one of the most transcendent acts we can preform to both strengthen our marriages and produce offspring while drawing near unto God. Yet sex has become taboo in our culture, partially in response to the free love movements of the seventies, and its commercialization. No longer does Sex represent communion with the essence of life but instead it is twisted into the altar of self gratification and obscenity.

I have to be honest and say that some of the reformation lost us a part of our religious heritage that we may never gain back, the idea of Sex and the Divine.

Though the book may not be inspired it is worth it merit as it is quoted in the Doctrine and Covenants.

Song of Solomon 6:10

10 Who is she that looketh forth as the morning, fair as the moon, clear as the sun, and terrible as an army with banners?

D&C 5:14

And to none else will I grant this power, to receive this same testimony among this generation, in this the beginning of the rising up and the coming forth of my church out of the wilderness—clear as the moon, and fair as the sun, and terrible as an army with banners.

Perhaps there is more to the Song of Songs than it seems

Don, using Barbara's desktop: I remember being amazed at the beauty of the Sheer ha-sheerim (Song of Songs) when I read it for my Biblical Hebrew class, though I didn't get to read all of it in Hebrew. Our instructor, a somewhat secular rabbi from Israel, told a story about the inclusion of the book in the first canonized version of the Hebrew scriptures. The comment was made that it was pornographic, and therefore could not be scripture, but a famous rabbi (I think it was Eliezar, but it's been too many years to remember well) said it was too beautiful to leave out, and offered the interpretation that the Bridegroom was G-d, and the Bride, His people Israel. The story may be muddled, but I share the sentiment.

Great work.

Post a Comment